Revisiting Richard Wright’s NATIVE SON to Understand Why Americans Choose Fascism

Is there really a compelling rationale for Americans choosing fascism this election season?

This question is one we really need to explore. And beyond looking for a good reason, we simply need to ask in a serious way why they did in a way that likely brings us to considerations outside the realm of rationality and which instead reside within a more fundamental emotional dynamic motivating Americans.

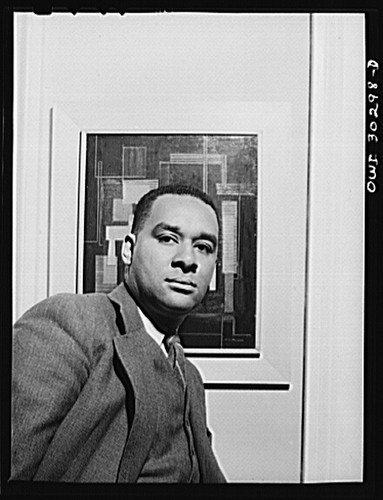

As a professor of U.S. literature, I tend to think literary works offer a lot of insights into the American character and cultural dynamics over time. When it comes to understanding Americans’ attraction to a fascism that would seem to promise nothing but punishment even for those who voted for it, Richard Wright’s landmark 1941 novel Native Son, through the development of its main character Bigger Thomas, may help us understand why the American voter chose a felonious rapist who espouses an authoritarian and retributive agenda over another candidate who speaks of ameliorative policies to address Americans’ real struggles, whether fully sufficient or not.

One can point out the foibles and insufficiencies of the Democratic Party or the Harris campaign, but that position doesn’t really seem to explain why Americans turned to Trump’s authoritarianism and hate.

Too often this question hasn’t been asked, or it’s been answered way too simplistically.

To lay the groundwork for exploring what Richard Wright has to say about this choice, let’s look at one of the dominant reflexes of scapegoating Harris and the Democrats.

In the news these days, we hear the pundits engaged in post-mortems on the Democrats’ defeat in the recent elections, mostly blaming Harris and the Democrats for their failure to connect with American voters and often excoriating the Democrats, typically in contradictory ways, for abandoning the working class.

Bernie Sanders stands out as the chief exemplar of this latter position. In a recent op-ed, Sanders at once accuses Democrats of abandoning the working class while also congratulating himself for having worked with the Biden administration to both build a pro-working-class platform and also actually enact measures and legislation to serve and support working-class interests, asserting,

As an Independent member of the US Senate, I caucus with the Democrats. In that capacity I have been proud to work with President Biden on one of the most ambitious pro-worker agendas in modern history.

So where’s the abandonment?

The Democrats, according to Sanders, did not message properly: “But, unlike FDR, these achievements are almost never discussed within the context of a grossly unfair economy that continues to fail ordinary Americans.”

The abandonment is apparently in the fact the message wasn’t clear enough, loud enough, substantial enough.

Look, I’ll be the first to admit that both parties have long been political creatures of the capitalist system and in league with corporate America. It also strikes me that this complicity has been a matter of degree, and that historically Republicans have espoused an untrammeled capitalism with no social safety net and little to no rights for workers or civil rights for that matter, while the Democrats have tried to provide buffers and ameliorations for the impacts of capitalism while also advocating for civil rights.

On the whole, the Democratic Party has historically tried to expand access to healthcare, protect social security, raise the federal minimum wage, legislate to create more fertile conditions for union organizing, sustain a woman’s right to choose, defend voting rights, and more–all of which Republicans historically have opposed and attempted to undermine.

So, one might say, regardless of the insufficiencies of the Democratic Party from a revolutionary perspective, the contrast between Trump and Harris is still clear, if not gaping and severe.

Sanders seems to disagree. Even while acknowledging that Trump is actually the enemy of the working class offering only more tax cuts for the wealthy among other nefarious objectives, he nonetheless asserts in another statement, "While the Democratic leadership defends the status quo, the American people are angry and want change. And they're right."

Were they right about the change they chose?

While we can argue with whether or not Harris simply defended the status quo, we do most definitely need to ask if Americans were right to choose fascism. Were they right to choose mass deportations, which will cost taxpayers dearly and cause more inflation by exacerbating labor shortages and costs? Were they right to choose a party and a president that supports “don’t say gay” laws, book bannings, and the abrogation of voting,civil, and human rights. Were they right to support a party that denies women the right to bodily autonomy and essential healthcare, threatening their lives? Were they right to disempower workers by undermining democracy?

As I’ve written before, it doesn’t seem very useful or productive simply to blame Harris and Democrats for not engaging voters. We have to ask as well what drew Americans to Trump’s fascism and compelled them to overlook these basic and very material differences.

Through his representation of Bigger Thomas in Native Son, Wright explores an African American population he diagnoses as hanging in a political balance, capable of turning either toward a brutal fascism or a more progressive liberatory politics. What will determine which way African America will turn? Wright brings us beyond questions of right and wrong and even of ideological preference to get to a perhaps more fundamental dynamic as he explores this question.

In Bigger Thomas, Wright represents an African American male effectively disenfranchised from and living on the margins of U.S. society, in a constant state of fear in America’s white supremacist culture and economy, and filled with shame and self-hatred having internalized racist norms and feeling blamed for his powerlessness and lack of possibilities.

At one point in the novel, Bigger is employed as a chauffeur for a wealthy white family, and as he drives through Chicago, Wright depicts the thought-feelings guiding his political consciousness:

As he rode, looking at the black people on the sidewalks, he felt that one way to end fear and shame was to make all those black people act together, rule them, tell them what to do, and make them do it. Fimly, he felt that there should be one direction in which he and all other black people could go whole-heartedly; that there should be a way in which gnawing hunger and restless aspiration could be fused; that there should be a manner of acting that caught the mind and body in certainty and faith. But he felt that such would never happen to him and his black people, and he hated them and wanted to wave his hand and blot them out.

Wright foregrounds here the fear and shame–and the desire to overcome these feelings–dominating Bigger. These controlling feelings seem to limit his imagination of a political solution to political, economic and social oppression to an authoritarian response–”to make all those black people act together, rule them, tell them what to do, and make them do it.” At the same time, he wants his and his people’s “gnawing hunger” and “restless aspiration” fed and satisfied. He yearns for “certainty and faith,” to live in a world where his aspirations have some chance of realization, but this desire is countered by a hatred for himself and his people that inspires a violent and self-annihilating impulse.

When he does hope, he seems only able to hope in authoritarian terms:

Yet, he still hoped, vaguely. Of late he had liked to hear tell of men who could rule others, for actions such as these he felt there was a way to escape from this tight morass of fear and shame that sapped the base of his life. He liked to hear of how Japan was conquering China; of how Hitler was running the Jews to the ground; of how Mussolini was invading Spain. He was not concerned with whether these acts were right or wrong; they simply appealed to him as possible avenues of escape. He felt that some day there would be a black man who would whip the black people into a tight band and together they would act and end fear and shame. He never thought of this in precise mental images; he felt it; he would feel it for a while and forget. But hope was always waiting somewhere deep down in him.

Importantly, Wright represents Bigger’s attraction to violent dictatorial rule as disassociated from any moral or humane code: “He was not concerned with whether these acts were right or wrong.” He simply wants someone, a strong man, to come and “end fear and shame.”

Notice there is no talk of any rational agenda or policy, economic or otherwise, for ending fear and shame. Wright keeps his analysis of Bigger’s political gropings on the level of feelings, not thought, not rationality. In fact, Wright is clear in letting us know that “he never thought of this in precise mental images.”

I think Wright’s representation of the dynamics of Bigger’s political consciousness offers an important insight for this moment.

While Sanders and so many others can critique Harris and the Democrats for their messaging, their platform, for abandoning the working class, the bottom line here is arguably no matter how loudly or strategically Harris might have shared her message or sharply contrasted her policy with whatever Trump has been selling, folks couldn’t hear it.

Wright’s analysis here in his portrayal of Bigger explains why no matter how many interviews or appearances Harris did to talk about her policy positions, people simply weren’t able to hear it through their feelings of fear and shame.

Bigger’s portrayal explains why Trump’s rallies, which were only rambling diatribes, perhaps proved successful. It explains why Trump’s campaign often didn’t even bother to talk about policy and ran millions of dollars in ads in swing states down the stretch about transgender “issues,” playing upon people’s phobias.

It explains Sanders’ incoherence, at once insisting he helped the Democrats build an ambitious pro-working-class platform and then blaming them for abandoning the working class in their messaging.

That message wasn’t going to penetrate the American rational mind. The rational mind wasn’t working so well, or wasn’t dominant when it came to processing information.

Just as Bigger wanted a strong man to simply fix things, so too did Americans this election. They didn’t want to hear the details of how or dwell on policy too long. So Trump’s simple message of “I’ll fix it” worked. Americans didn’t want the why; they just want some strong man to fix things, regardless of the “right or wrong” of it, regardless of who gets hurt or how inhumane or cruel the means are.

Americans, if viewed through Wright’s words here, are not in the mood for participatory or even representative democracy. They are and were ready to surrender power to a strong man and unleash might regardless of right.

Wright’s analysis here is largely echoed in Arlie Russell Hochschild’s recent book Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame, and the Rise of the Right, in which she argues precisely that Trump and the Right are able to speak to and play upon the shame so many rural and disenfranchised white workers feel, blaming themselves for their lack of success, and get them to turn that shame into outward anger toward a somewhat mythical “liberal elite” that, the false story goes, cares more about people of color, women, LGBTQ people, and the other identity groups, but not them, white working-class males and their families.

Sanders’ incoherent rhetoric, unfortunately, largely reproduces the Right’s arguments.

If there is a lesson for Harris and the Democrats, it may be in messaging. If we listen to Wright’s smart analysis–and Hoschschild’s too–the Democrats need to couple their policy messaging with a mode of communication that touches these emotional levels on which American voters are operating and figures out how to channel those emotions not into hate, anger, and violence but into hope, empathy for others, and a politics of love that can feed their real hunger.